I had an interesting chat online with some other journos yesterday/last night about the place (or, in my view, lack of place) of paid PR propagandists like Matthew Hooton as ‘pundits’ or ‘panelists’ in news and current affairs shows. (Click the image below to read around the conversation on Twitter. There was quite a lot of to-and-fro.)

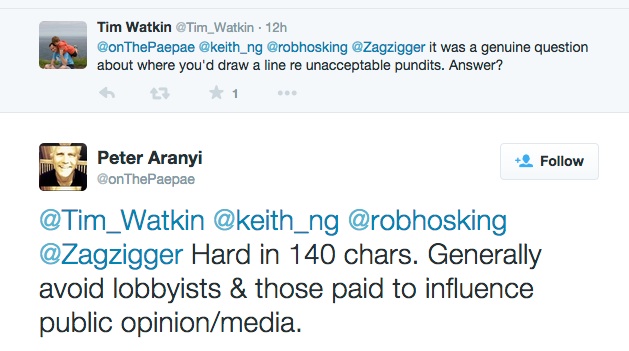

At one point TV3’s The Nation producer Tim Watkins quite fairly asked me where I’d draw the line re unacceptable pundits … to which I answered:

Here are some thoughts from someone else who’s thought about it — Nicky Hager in 2008…

Imagining a world where the PR people had won

by Nicky Hager

a speech to Sociological Association of Aotearoa New Zealand Conference, University of Otago, November 2008.

Those of you who grew up in New Zealand will share my experience of a country of clean rivers and streams. We could swim in any river, drink from almost any stream and spend time by the smallest creek trying to catch little freshwater native fish. I remember as a child hearing about countries like the United States where they had “water pollution”. It seemed remote and unthinkable that New Zealand would ever have such problems.

As you know, New Zealand today, the land of water, has serious water pollution problems. A lot of rivers are too polluted to swim in, much less drink. Even some major ground water supplies are polluted. Lake Taupo is in risk of biologically dying. The creeks are mostly too polluted to have native fish. Many of them have dried up and disappeared. Even more surprising, there are water shortages. In Canterbury some rivers have so much water taken out of them for industrial farming that they disappear altogether in dry years.

These problems have grown slowly — too slowly to catch attention or prompt much concern — and then they have accelerated in the last 20 years when restructuring of the New Zealand economy led to changes to land use and farming practises. Until recently there was no awareness outside a few specialists and now suddenly people are waking up to what’s been lost, and how it changes our lives. But even now the major water users and polluters unsurprisingly are still denying anything’s wrong.

This, I will be arguing today, is a good analogy to what’s happening in the democratic sphere. We live in an era where the public spaces are being crowded with paid spokespeople, spin and trickery; where news and political discussion are being polluted by the glib outpourings of ever growing numbers of PR people; and where the public spaces available for real democratic activity are drying up.

These problems have grown slowly — too slowly to catch attention or prompt much concern — and then accelerated in the last 20 years as restructuring of the New Zealand economy has led to redistribution of power and resources and changes to our politics and media.

My subject for today is considering the CUMULATIVE IMPACT of the growth of public relations, and particularly its cumulative impact on the media and the other public spaces where politics occurs. I will give an overview of the trends: more and more paid manufacturing of news, more and more paid voices in so-called public discussion, increasing sophistication of manipulation, more media management, more fake community groups, more scripting of politicians by unseen advisers and so on. My question is, how much is too much? When is the system broken, the river polluted?

I will describe some of the range of influences that undermine modern democratic society. It is largely bad news but later I’ll talk about where I see the hope.

The fundamental squestion I’m discussing tonight is whether democracy is being rendered non-functional in the advanced democratic societies where we might imagine it is strongest.

My reason for talking about this here, at a sociology conference, is that I will be skimming over various issues that I believe deserve much more work and public discussion. Many have a bearing on the sorts of subjects that I can see from the conference programme others here work on. I hope you may be encouraged to work on some of things I raise.

From the 1930s until the 1970s, most PR in New Zealand was from the Government, particularly the Tourist and Publicity Department from 1930 and National Film Unit from 1941. In the early years there was a tiny number of private PR people and lobbyists: maybe one person for the liquor industry, another for the Manufacturing Association and everywhere else! The numbers and influence of professional PR people have grown a hundred fold since then.

Today there are PR units in every government agency, Minister’s offices, local government, universities, crown research institutes, state-owned enterprises and so on. There has been even greater growth in the private sphere. Private PR firms began to appear in the 1970s and 1980s but since then there has been exponential growth. In Wellington, for example, there are now about 50 PR companies involved with hundreds of clients and campaigns.

On top of them there are numerous PR contractors, in-house PR people in large companies, specialised lobbying companies, numerous industry lobby organisations, law firms that offer PR and lobby services and a wide industry of support services that further enhance the advantage to those with the money to pay.

Looked at isolation, most PR seems relatively innocuous or at least just part of “vigorous” debate and a “contest ” of ideas. And this is true. We probably all know PR people. Most of them aren’t doing anything very evil (although I will talk about the more destructive sorts in a little while).

They’re just helping some client get their message out. But it’s like the example of water. A stream can maybe handle the runoff from one dairy farm and a river handle irrigation for one new dairy farm. Then suddenly – and it does happen quickly — when there are lots of new dairy farms the rocks all get slimy in the stream beds, there’s not enough water for other river users and large dead zones start to appear out to sea adjacent to the river mouths.

I will work my way towards the subject “imagining a world where the PR people had won” – and whether they have – starting with looking at the political/media environment we live in:

First, news. Anyone who works in or near the media or PR knows that most news items on a given day are not the product of journalism. Although they are presented by news organisations as something they discover and report, most have been scripted, timed and stage managed by paid PR people. There have been some good studies comparing each day’s press releases with what is seen in the media. Much goes straight from the PR people into the news without any significant journalist input.

Recently I was helping take a journalist training session and one of the chief reporters there said this is so common that he has introduced a rule of printing out press releases before assigning them to reporters because then they at least cannot just cut and paste directly from the press release. His modest goal, slightly rewritten press releases! In US, PR firms are now making complete TV news items — and the TV stations are running them as news.

It’s hardly surprising. The number of PR people goes up and up, while — as I’m sure you’ve heard many times — newsrooms get smaller, budgets are squeezed and the average age of journalists gets lower. Of course the news media sometimes does something independent and even spectacular, but most of the time, on nearly every issue, the PR people are better resourced, more numerous and more focussed. The result is that for most new items, the public should be asking who is behind the item, what are their motives and why now?

But it is much wider than individual pieces of news…..

Nowadays a whole issue or whole campaign can be created and run directly out of public relations offices. I will give an example. One of the biggest public debates in recent years was over GE foods, with groups formed all over the country and quite strong public support for the GE-free movement. In the media it looked like a two-sided debate, but one of those sides was almost entirely manufactured by PR professionals.

At the beginning in the 1990s, the pro-GE lobby was run out of a Wellington PR firm called Communications Trumps. The first incarnation was a body with the friendly name Genepool. It described itself as an “independent education trust” to give the public impartial information to balance the emotive and extreme views of the GE-free groups. Genepool played a vigorous role until 1999 when info was leaked by unhappy staff members about Communications Trumps covering up genetic engineering experiments on salmon that had gone wrong in Marlborough — and then later that the ‘independent education trust’ was actually being funded by the giant US genetic engineering company, Monsanto.

Genepool was quietly closed down but a new front was immediately planned.

Communications Trumps called a meeting at law firm Russell McVeigh to plan the formation of a new pro-GE lobby, the Life Sciences Network. Its first strategy paper was prepared by the PR firm Consultus New Zealand, branding the GE debate as “characterised by emotion not science” and setting as their goal to make the Life Sciences Network the pre-eminent and credible advocate on the side of science. But it was still not run by scientists. It was headed and run during its four or so years of existence by a PR consultant from Consultus New Zealand named Francis Wevers. It was aggressive and focussed in its tactics.

Like all major PR campaigns, the PR staff were backed up with a range of resources such as media monitoring, select committee monitoring, marketing companies, polling companies, economic research companies, contract writers and on and on that provide all the backing to the well-resourced lobbies that money can buy. One of the services PR campaigns like to buy in is senior media figures, who are brought into the campaign in roles such as strategy advisers and media coaches. With LSN, the supposedly independent commentator Colin James was very well paid for being its private political advisor.

The Life Sciences Network refused to declare who was putting up the money. but it was awash with money, including hiring a floor of a building directly next to the Royal Commission of Genetic Modification. By pumping out press releases, flying in a succession of overseas experts who supported their position, commissioning reports and opinion polls, cultivating allies close relations with the Labour Government and working to marginalise their opponents – including any scientists who spoke out questioning genetic engineering — this PR operation came to dominate the issue and eventually won: a few PR people and lots of resources beating a nationwide movement with a high level of public support.

After their victory, LSN had served its public relations purpose and was closed down. Its head, Francis Wevers, moved on to head the Gambling lobby in New Zealand — an organisation called the “Charities Gaming Assn” — where recently he could be heard vehemently denying that gambling addiction produces a large proportion of pokie machine profits. Wevers was subsequently honoured with the Public Relations Institute of New Zealand’s 2005 Supreme Award for excellence in public relations for the Life Sciences Network.

Imagine dozens of campaigns like this going on all the time, on every controversial subject and even more where it suits the clients to keep a low profile and avoid public debate.

Whenever there is a big issue like genetic engineering, or a controversial industry, we should assume that somewhere in the background there will be PR people like Francis Wevers. The lobby doesn’t need to have majority public support, or any public support at all. All it needs is lots of money to buy in the skills and resources of these sorts of PR people.

This can look like diversity, with lots of different voices, like a contest of ideas, freedom of speech. But often it is only the paid voices coming through. Then it’s diversity in the way that a plantation pine forest has diversity… there are some ferns and shrubs in the understory, and a few native birds. But the structure and all the dominant trees are the result of commercial forces.

My point is… we should be considering the cumulative impact, on issue after issue, of having dozens of these sorts of commercially constructed political and social-engineering campaigns filling the airspace and dominating politics.

We should also consider the cumulative impact on the public spirited members of the public who try to contribute to the politics of their country and find themselves up against this sort of slick, well-resourced PR campaign. On one side voluntary people, on the other the ability to buy in endlessly re-energised professionals.

Another example is climate change. The Labour-led Government’s efforts to introduce a carbon tax met a massive counter-campaign from all the large emission producers. Eventually the pressure of opposition led Labour to drop the plans. There was an interesting university study of this anti-carbon tax campaign that found that nearly the whole thing had been coordinated from one Wellington lobby firm (Saunders Unsworth), again mostly by one very well resourced and energetic PR person. Moreover, it found that, unbeknown to the public, the campaign had been organised by none other than the coal industry, which chose not to show its involvement but had an obvious vested interest in killing measures to control climate change. To give a very different example, the campaigns behind the law and order hysteria in this country also warrant exposing.

As PR people say to each other: the best PR campaign is the one that no one realises is going on. Media organisations run the press releases and quote the well-timed visiting experts often without stopping to consider and report on the PR campaigns in the background.

An example of this is the completely unanalysed elimination of the politician Winston Peters at the 2008 election.

As I already said, with most PR campaigns there isn’t a public campaign on the other side and the industry campaigns are virtually unopposed. An example of this is the finance sector, who have long-term PR strategies to promote the interests of the foreign finance companies. One of their tools is paid public voices, who are the main voices heard commenting in the media on most financial and economic issues — naturally enough pushing the sorts of policies that aid profits for finance companies. These voices are so normal, and accepted so uncritically by most media, that we don’t even think of “BNZ economist” and “ASB economist” and “Bancorp economist” as industry lobbyists.

Another example is the Real Estate Institute, whose vigorous long-term PR strategies are working diametrically against what many of you would care about in housing. It has, for instance, run a long-term campaign to avoid capital gains taxes in New Zealand, a campaign that benefits from the fact that no one is even aware there is a campaign going on.

Defenders of Public Relations say by about this stage: ‘Why shouldn’t everyone get to have their say? That’s democracy.’ That’s true up to a point, but it depends whether the paid voices effectively drown out or crowd out the rest. More and more, they do. But there’s more than this. In my years of studying PR, I’ve discovered that a lot of the effort doesn’t go to helping their client have a say, but into trying to stop their political opponents from having a say. “Communications” people who are anti-communications. The LSN specialised in this. Some of you may be aware of a clear example of this in my 1999 book Secrets and Lies.

The book, based on hundreds of leaked PR papers, describes another campaign devised and coordinated by PR people. It included a fake community group (the Coast Action Network), lavish funding of co-opted experts, and all the usual spin. Their PR strategy was clear: public support for cutting down old native forests full of kiwi and other rare species was firmly against them. They couldn’t win the debate so over half the work went into trying to silence their opponents. Obviously if their was no debate, there would be no pressure for change.

This PR activity, of silencing the public where it doesn’t suit a client, is naturally something that will be done quietly. However, I think that a huge amount of this goes on and we live with the results of it in the kind of society we have.

I believe that to understand current New Zealand society, one of the most important mechanisms to understand is the past and present attacks on certain groups of people. For example, one of the vigorous PR vehicles in the 1980s was New Zealand Business Roundtable, NZBR. It claimed of itself that it was purely a source of information and analysis, but one of its main tactics was active attacks on anyone prominent or influential that did not support its beliefs. Many people were hounded out of positions of influence by its efforts.

Because the winners wrote lots of this history, these events need more analysis to understand the long-term effects. However there is a lot of evidence of the journalists who got repeated attacks and found themselves marginalised at that time. The same with public figures like economist Brian Philpott, who was hounded out of the Wellington newspapers. One Wellington lobby firm specialised in pressuring journalists (it’s co-founder is still a dominant character in Wellington PR and lobbying).

The same thing happened in universities and the public service – with nasty attacks on critics of Rogernomics and behind the scenes manoeuvring to undermine their employment. Many people were pushed aside in this way, while other were favoured and promoted. NZBR head Roger Kerr went onto VUW council from 1995-99 to continue this process, actively investigating and making life difficult for lecturers who were outspoken against the policies he believes in.

A university economist told me recently that there had not been a single appointment of a left-leaning economist to any university department in New Zealand for about 20 years. If correct, this would mean that – even though New Zealand has moved a lot since the 1980s and 1990s — econ students today are still getting an almost uniform diet of free market ideology.

There was an important moment in this chilling of political diversity in the late 1990s, that has affected journalism ever since.

In 1989 there was a current affairs programme: Frontline: Pro Bono Publico/For The Public Good that looked at the links between 1980s Labour Government politicians and key businessman who were benefitting personally from its economic reforms (such as privatisations). Looked at today, the programme looks unexceptional, but at the time it was highly controversial. TVNZ was sued, the journalists were attacked from many directions and TVNZ restructured its current affairs into the Auckland offices to ensure that nothing like it happened again.

The lead reporter eventually left the country. He now works for Australian ABC radio in Darwin. TV current affairs and TV journalism has mostly been cautious and populist ever since. This is an important piece of NZ media history. Like universities, we are still living with the effects 20 years later. A year after the Frontline programme Richard Long took over as editor of the Dominion newspaper and turned it to the right, issuing to reporters a list of people who would not be quoted in the paper any more.

To understand New Zealand of today we need to be aware of these activities over the last 20 years — those who were promoted and those pushed aside. Many people in top roles in unis, science, media etc today are products of that time. We are, in part, still living in the world made by the free market lobbyists and their aggressive political strategies. This deserves more study and discussion.

Alongside this there has been a literal shinking of the public space available to other voices.

At the same time as paid interests get more and more outlets, the space for normal public involvement in politics seems to be getting less. Have other people noticed this? In my city, Wellington — supposedly the political centre of the country — there used to be a pleasing clutter of political posters on all sorts of subjects … today there are virtually none. It recently became clear why this was. The WCC had made a rule that NO posters are allowed on any lampposts or other sites in the city, and if it finds any it has them cleaned off straight away and sends the bill to the group concerned. It gets worse.

There are some public poster locations in the city, but the council privatised them. They signed a contract with a private poster-sticking company that gives it exclusive rights to the public spaces — meaning that they have just become as extension of commercial outdoor advertising. Not only that, the council stipulated that the private poster company is not allowed to put up political posters. These are the decisions of people who see the world through corporate eyes — seeing lspace for paid advertising and messages all over the city — but don’t give a single thought to there being public space, democratic space.

To me this epitomises the wider problem: the DE-LEGITIMISATION OF POLITICAL ACTIVITY (including the denigration of ‘activitists’).

Think how weird it is the PR people get media space and credibility as political commentators while people working for the public good are called “activists” and treated with suspicion.

It is the wrong way around.

The de-legitimisation of political activity is also seen in the DISCOURAGEMENT OF POLITICAL ACTIVITY BY PUBLIC SERVANTS…

When I first got involved in politics in Wellington, the organisers, spokespeople and writers for public campaigns were often public servants. Today there are many examples of where public servants are made to feel they’ve done something wrong — or are actively punished — for being involved in politics as a citizen outside their work time. I meet public servants who are fearful about politics for this reason. The message, at the centre of government, seems to be all wrong. I think this needs more investigation.

This has the effect of removing large numbers of informed and concerned people from active involvement in politics. I think it should be a national objective to have as many people as possible feeling positive and empowered about being active citizen. But, if anything, political activity is being framed as something suspect.

You know this, but I should also note in passing that being outspoken as an academic isn’t always easy, even though it should be a job requirement in a healthy democracy.

SOMETHING’S WRONG. IT’S AS IF THE MESSAGE IS THAT POLITICAL ACTIVITY IS BAD. IT’S AS IF MANY PEOPLE IN POSITIONS OF AUTHORITY DON’T ACTUALLY BELIEVE IN DEMOCRACY, DON’T RESPECT THEIR FELLOW CITIZENS…. I FIND THIS REMARKABLE AND WORRYING.

In contrast, let’s consider what we do hear in the media…

One aspect of the narrowing of public space is, of course, the media itself. Foreign ownership, the commercialisation of TVNZ, the privatisation of RNZ’s commercial network and a narrowing of the range of publications in New Zealand have all reduced the democratic space. The country’s main reasonably intellectual and progressive magazine, the Listener, has become a lifestyle magazine with National Party politics. There’s no Guardian or Independent. New Zealand has almost no space for ideas even vaguely left of centre. The risk is that this becomes normal and we no longer even notice what we’re missing.

Actually, I think it has already become normal and it’s not being noticed enough. Let’s look at the political range of voices in our media….

NZH: Fran O’Sullivan, John Roughan, Colin James, Garth George on the right, with less ideological voices being Tapu Misa and Brian Rudman.

Dominion Post: Richard Long, Rosemary McLeod, Bob Jones, Simon Upton, Matthew Hooton, with Chris Trotter as almost sole voice from the left.

The Listener: Jane Clifton, Deborah Cone Hill, Bill Ralston, Joanne Black, with a little economic column hanging on from Brian Easton.

On Newstalk ZB (the privatised RNZ network, that many more people listen to than RNZ) the main voices are three right wing bigots: Paul Holmes, Larry Williams and Leighton Smith, and their regular commentators such as Graeme Hunt, Jane Clifton and Michael Bassett.

And so on. Matthew Hooton also appears regularly on Radio Live, RNZ Nine to Noon, the Sunday Star-Times and on television. And who is Hooton? A full-time PR man – a prominent figure in Brash’s National Party, Timberlands, pro-tobacco, pro-nuclear ships and many contemporary clients via his Auckland PR firm. A measure of the lack of balance in the media is how often we hear him.

This media environment naturally has direct effects on politics and generally on what ideas have dominance in society. Things they don’t like tend to be mocked and their prejudiced world view is normalised. Without other voices, or enough other voices, these views prevail.

This is part of how a modest little private member’s bill about child violence, section 59, become a huge and foolish hoohah about an ‘Anti-Smacking Bill”?

Why, because there are so many voices repeating that point of view. Why do we “know” that the Electoral Finance Act is an outrage against freedom of speech? Because we heard it so often. I think this is crucially important for understanding our politics, for understanding the way lot of issues are regarded, and for understanding what needs to be done about it. Think of the issues you care about. Also there is: Why are critics of free trade crackpots? Why are Green Party policies loopy? Why did Winston Peters’ dodgy election finances get literally dozens of front pages this year and the National Party’s, after my National Party book came out, get almost none? Lots of it is about the voices that have come to dominate the public space.

We’ve all recently endured an election campaign that was ‘boring’, the press called it, artificial and lacking real debate. The campaign was a strange uninspiring experience, with journalists hanging around waiting for slips or unusual incidents, since the the daily photo opportunities were boring. But this misses the point that the nature of the election campaigning is very important, that the ‘boringness’ needs to be analysed and challenged rather than writing off elections, democracy, as being poor entertainment for the easily bored masses.

What I found in my last big project, the book The Hollow Men, is that this is mostly deliberate…….

MINIMISE AND AVOID POLICY LINES/artifice/”crisis management” approach to issues

IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT

UNDECLARED STRATEGY

(Then there is the familiar irony: after avoiding policy as much s possible, years of negative attacks instead of debating policy and presidential-style impression management over substance, the politicians who win the election immediately claim they have a resounding public endorsement for their policies).

…. Little wonder that there was almost the lowest voter turnout in a century. I take this as sign of damage being done to the democratic sphere.

These were just a few of the subjects my book The Hollow Men. If you were one of the people who was put off by the National’s Party’s damage control, and believed that the book was just about Don Brash, or his e-mails, or “all made up”, I urge you to take a look at the priceless inside picture of the thinking and workings of a political party that my inside sources provided.

There are many other areas of PR — crisis management (at its worst the art of distracting, diverting and bluffing a client out of responsibility for a crisis), environmental and social responsibility programmes (usually the least environmentally or socially responsible companies trying to do some ‘greenwashing’), producing resources for schools (a particularly insidious area), numerous aspects of what is called “government relations” and sponsorship, which sounds innocuous, or even altruistic, and usually isn’t.

In all these ways, bit by bit, they shape our society. They become normal, just part of the landscape. We don’t notice what is missing, or the underlying distribution of power that is shaping what we see.

I think my title probably sounded overly cynical. “Imagining a world where the PR people had won.” But let’s imagine what that world would look like and judge how real it sounds. In it, most messages heard in public would come from PR people. In it, the public actions of powerful individuals from politics and business would be planned and scripted by PR people. Answers by politicians would have that artificial sound of scripted lines. Election campaigns would be controlled and scripted. Even ‘protests’ and ‘public campaigns’ would be the product of PR people. And other voices, groups and ideas would be pushed to the margins.

In other words, when we imagine a world where the PR people had won, we are already there. To a considerable extent, the well has already being poisoned and the streams are drying up.

A symptom or consequence of this is how many people feel about politics. I heard a story a few years ago about a new resident in Auckland, from China, who cried the first time he was able to cast a vote. How do New Zealanders feel? Many say they “don’t like politics” or “don’t like politicians”. This could be dismissed as apathy, or complacency, or cynicism. But I think it’s more accurate and helpful to recognise the things that alienate people from politics, that show them they don’t matter, that disappoint them when they do go up against the Life Sciences Network or whatever and try to make a difference. When people “don’t like politics” it’s not about them, it’s about the poor health of democratic society.

But this anti-democratic kind of politics of course hasn’t won. It is dominant — so dominant, we barely notice. But it hasn’t won. History goes on and society is made of many, many parts, some getting better at the same time as others are getting worse.

What can we do? A lot of what I’ve talked about can’t be changed in the foreseeable future. But some can. And, more important, other things can happen that counterbalance the influence of the paid voices and politics.

1. Talk about these issues, as they affect your specialties and more widely. Study the influences. Talk about it in public, which is always the first step towards change.

2. Relegitimise democratic politics. Stick up for it. Talk about it. Take part. Unless it is named and explained, it cannot be defended. Unless some people lead by example, how are other people going to regain hope about their own political selves (hope is a casualty is all this).

3. De-legitimise public relations and the anti-democratic style of politics I’ve been talking about. It needs to be named and discredited. Politics by secrecy, spin and manipulation are not worthy causes but they need to be held up to the light or they will continue unchallenged.

4. Find, promote and support different people to be public voices in our society. We need to encourage and promote more people into these roles – not leave it to the Matthew Hootons. Sometimes (you may know the feeling) I wonder if all the intelligent people have gone overseas or something and we’ve just been left with the lineup we see in the media. Then, of course, I immediately meet marvellous, interesting people all over the place. The problem isn’t that they don’t exist – it is that they aren’t as conspicuous as those currently getting the public space. The answer here is for others to do it (for example academics!), learning the skills and building up the confidence to get out there and use their voices and power. We also need to support the people who speak up. This has to be a joint effort against the current dominance of a narrow range of voices.

5. Not lose hope ourselves about democratic politics. I think a lot of people privately feel pessimistic about politics. My experience is that there are always numerous idealistic and principled people who care about the kinds of issues being talked about at this conference. There are many, many people, young and old, who are not represented by the cynical, dumbing down influences. When politics feels unsatisfying, they may seek other outlets – like the astonishing numbers of social service and conservation groups operating invisibly all over the country – but the people are there waiting for better things than currently seem to be on offer. We should get hope from them.

PR politics mostly works by tricking, dodging or discouraging the public, not by winning their hearts. There are lots of people waiting for things to be different.

reproduced from www.NickyHager.info — “Imagining a world where the PR people had won”, a speech to Sociological Association of Aotearoa New Zealand Conference, University of Otago, 26th November 2008.

What I love about Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, is that it is always 1984, and no one dares question it.

An interesting read.

I think that the last extreme lefty government in economic terms in NZ was probably Sir Robert Muldoon’s government from 1975 – 1984. In the 30 years or ten odd elections since then, both National and Labour have run economically centrist governments. I personally doubt that New Zealanders will ever elect an extreme lefty government again.

I suspect that Mr Hager senses the same trend as I do. It is possible that the extreme lefties are never going to win power again in NZ…

I think that his article is really an explanation of why he thinks this may well be the case. His answer, I think, could be summarized as follows – the people have been tricked and cheated into voting for the wrong people. I see Mr Hager’s views as comparable to a silly horror movie I saw recently, where most of the population were actually aliens wearing masks, and the hero was the only one that could see the aliens behind these masks.

Alas, Mr Hager’s view could be seen as slightly patronizing and condescending – voters are systematically fooled into voting for the bad guys. His view seems to be that the people only vote for centrist balanced government because of a right wing conspiracy, which controls the media and the people in a vice like grip. Presumably, if the extreme lefties got a fair crack of the whip, they would win instead.

I personally think that the election of centrist governments in economic terms is a global phenomenon, because voters are quite smart. They generally choose what works better. Of course, the Hager’s of the world have an alternative view, and instead view these outcomes as a global conspiracy, with the voting populations being manipulated everywhere.

In the end, I do not like Mr Hager’s views, for one main reason. For the last ten elections, centrist governments have been elected each and every time in NZ. Mr Hager cynically refuses to accept this is fair. He arrogantly casts aspersions on both the democratic system and the voting public’s choices.

The essential problem with the extreme left is they refuse to contemplate that the reason voters overwhelmingly reject them election after election is that they are wrong. Instead, they decide their failures are a result of right wing conspiracies.

Does the delusional nature of the extreme left matter? I think that it does. Democracy is harmed by the fact that these guys are completely unelectable. National has now won three elections in a row, and I would really like them to lose the next one. In my view, four election victories in a row would be bad for democracy. The problem, of course, is that the extreme left (the Greens et al) cannot be allowed any power, because they are dangerous vandals, who want to smash technology and live in caves.

Instead of whining and blaming the failure of the extreme left on the system, I think Mr Hager would better serve NZ by admitting his extremist policies were unpopular, and adopting more balanced and reasonable ideas.

Rgds,

*p*

Hi Poormastery

Thanks for sharing your point of view about these matters.

I always look askance at arguments that rely as a first step on painting opposing views as “extreme”. It’s often a not so subtle tactic to marginalize a position and to undercut it.

Weren’t the slavery abolitionists extremists?

Weren’t the suffergettes?

Weren’t family planning clinics?

Weren’t homosexual law reformists?

Weren’t those who agitated for proportional representation?

What about Maori Sovereignty/Treaty of Waitangi settlement?

Just as were the neo-liberal “free market” Chicago School of Economics (cough) reformers like Roger Douglas.

The legend that under Muldoon NZ was second only to Albania as far as having a tightly-managed economy is concerned is of course probably bogus. Your description of that gray & beige overwhelmingly male conservative government, where homosexuality was regarded as a slur fit to destroy an MP’s reputation, unionists were reviled as communists and “reds” (and really did visit Moscow for socialist congresses) and art was a nickname for Arthur and no more, as an “extreme lefty” government is of course, silly.

Muldoon was a centrist too, and a populist.

But just as a teenager needs to individuate from his or her parents, the Rogernomics/Reaganomics/Thatcherism drive — to sell off state assets and enterprises (usually cheaply), reduce the ‘size of government’, cut taxes and introduce ‘user pays’ — all cliches now, came about in part by PUSHING AGAINST THE PAST.

Of course Muldoon’s economic policies came to be criticised. But, as you so aptly point out, he was elected again and again … and was tremendously popular — until he wasn’t.

—

I tend to agree with Hager’s view that democracy has been subverted by venal and cynical PR & marketing “messaging”. The cold-blooded attacks on dissenting voices and the terrorizing into submission of public servants — to stay out of politics — are real factors.

The Dirty Politics thesis* seems sound. Political players are using deceit and soundbites to manipulate the media and the constituency,

– P

*Have you read the book poormastery? if so, what were your impressions? If not, why not, may I ask?

The new ‘right-political-swing’ has little to do with ideas – it’s all about money and nothing more.

Deceptive politics by various commercial enterprises has become an art form in the United States. It works well and is being duplicated the world over. I see it in New Zealand just as I have in the United States.

My experiences living in the United States has taught me to be rather cynical when it comes to politics and its associated news media. I don’t watch the popular news anymore, instead I have gravitated to the free, public news media, which does not fall under the influence of the of the few commercial broadcasting giants (though, they’ve been trying to squash it) http://www.usnews.com/debate-club/should-government-spending-for-pbs-be-cut

The real trick to understand what’s going on is to “follow the money.” No one entity has more money than a government, and someone somewhere finally figured that out. Now we are seeing more and more public services tied to for-profit corporations in some way. A good example of this is the privatization of prisons. http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/jun/13/aclu-lawsuit-east-mississippi-correctional-facility

I’m opposed to politicians who argue that selling public assets are good for taxpayers. The reason is simple. I, as a voter, can replace a politician or even a whole government if I want, but what the heck can I do about a contracted private company or the individuals that run it but complain?

Private toll roads are becoming all the rage in the USA now, http://usa.streetsblog.org/2014/11/18/the-indiana-toll-road-and-the-dark-side-of-privately-financed-highways/ My own experience in my own American city is that these private entities expect indirect support from all available public resources for their good faith public works. In the case of a private road, who polices it? Who cleans up after an accident? Why county police and firefighters of course, who else would do it?

The new ‘right’ is capricious but lazy. They want money and nothing more. They will drain a city, a county, or a country’s public coffers quickly, giving the same service the government should have given, regardless of whether that service is good or bad.

It’s good capitalism – leaching from a government. In fact, it’s the best capitalism because a government has an unlimited budget, if it wants.

Aren’t we told that government is big… cumbersome… useless… It’s an inefficient Goliath whose head does not know where its tail is. And no matter who we vote for, nothing changes. Sure, these are all good talking points – and while we are busy talking about it, behind the scenes, money, siphoned away from the very same government vilified by those very same talking heads, goes indirectly into the pockets of those for-profit corporations who claim to be champions of capitalism.

It’s funny when you think about it, but the joke is on the public taxpayer and no one else.

Thanks for dropping by. You’ve touched on a subject that’s alarming me and more: private prisons.

I’m hearing things about how the private prison at Wiri is being *run* which are greatly disturbing. That’ll be a topic for another time.

This week, there were some unexpected announcements of Corrections Department facilities being closed down/not re-opened because bringing them up to standard was seen as a less optimal idea than sending extra ‘clientele’ to the privately run prison — funded, just as you suggest, by the taxpayers.

-P

Peter,

I did not realize that describing either Mr Hager or the Greens as extreme was even slightly controversial. We will need to agree to disagree on this one.

Nor do I accept that Sir Robert Muldoon’s economic policies were in any way centrist – I still stand by the belief that my “extreme left” description is far more accurate.

*Have you read the book poormastery? if so, what were your impressions? If not, why not, may I ask?”

No, I haven’t read Mr Hager’s book.

I don’t read many books by NZ politicians et al. I read one of Roger Douglas books decades ago (maybe it was Toward Prosperity), but this was more about what policies he thought would be good for the country, rather than a lament about the unfairness of the system or the stupidity of voters.

Enuff!

*p*

Poormastery

“No, I haven’t read Mr Hager’s book.”

Gee, I don’t mean to embarrass you by that question. I think you’d find Dirty Politics very interesting. Here’s a link to the kindle version (not an affiliate link). Check out the reader reviews.

– P