James shuffled slowly to the edge of the railing. He was afraid of what he might find. No human could survive in this atmosphere without the proper apparel. The girl had been wearing a dress of all things! Something like one might wear to the summer picnic at the lake! James gripped the railing, knocking his own dust cloud into the thin dark air. He peered over the edge. The black cave-like hulk of the giant space below plunged downward into nothingness. If there was anything hiding over that precipice then it hid far beneath him in the blackness below.

James stepped back from the railing puzzled. He had seen the girl. No doubt about it. And, here and there, is the evidence of her presence he thought, looking at the scuff marks in the film of dust that was almost fifteen hundred years thick. He checked his atmospheric readouts: 100 Kelvin, pressure readout of 20 kilopascals, and 0.8 gee. These numbers were to be expected, nothing was out of the ordinary, but the girl… No amount of atmospheric accounting could explain her.

James pondered the encounter. All paths led to a conclusion of fancy. There was no girl! His continuing nightmares had been playing havoc with his sleep; he was fatigued, nothing more. There was no girl! Also, James had the nutritional issue from the lack of real food; his diet of algae — it could not be good for the mind. There was no girl! He had imagined her — that was all – a waking dream, nothing more. He turned back to the train and stopped dead in his tracks, there, etched into the dust, was the drawing of an arrow.

Scuff marks on the railings he could pretend, were made perhaps by an object falling from above. This was a dry-dock after all, and there were bound to be gantries, cranes, scaffolding, and other heavy manufacturing equipment hidden in the darkness above and below him. Scuff marks have no definition; they could be attributed to anything. It was conceivable that some object, at some point in time, fell from above, struck the railing and continued on into the abyss below. But this! This arrow was astonishing!

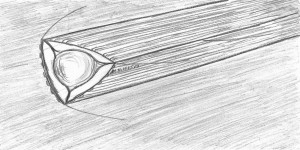

James stood stock-still and studied the arrow closely. The dust about the arrow was untouched. No footprint or blemish scarred its virgin face. Nothing betrayed the person or persons who put it there. He could see its groove in the dust; it had a childlike pattern to it, curved, as if a single ungloved finger had made it. Little telltale ridges in the dust had been left where the artist had lifted their finger up… up and away from the boardwalk and out of the dust. The arrow was about a half meter long; the arrowhead proportional to its length.

James took several photographs of the arrow with his helmet-cam; he edged about it carefully, photographing it from all angles, he was careful not to disturb the surrounding dust. He would look at these later; to be sure he was not imagining it. He was gathering evidence – evidence of what? A phantasm? Perhaps he would try and contact Moreland or Bingley? Send them the “evidence.” Bingley yes, but not Moreland; he was, to tell the truth, a little afraid of Catherine Moreland. Of the two, Moreland seemed to be the friendlier and the more approachable, but not really. It was an act. James decided that Catherine Moreland always wanted something — something she could use — something for herself. The drawing of an arrow in the dusty cavern of the Bethlehem dry-dock was not useful. It provided nothing to the political ambitions of Catherine Moreland. But Bingley — Bingley would listen. Bingley could provide him with the experienced adult-like guidance he sought. And Bingley, he felt, wouldn’t confide their secret to Moreland either. He wouldn’t inform Moreland because Bingley himself would not want to look… foolish. He finished this last part with the realization that this dusty arrow, this arrow, was for him and him alone – and to wherever or whatever it pointed was also his…

He remembered the voice he had heard before the elevator had imploded. Not a physical voice, but like the apparition of the girl, real enough. The voice had made him act. The voice had saved his life. The physicality of the arrow transcended the voice in magnitude. Voices come and go, but this… this was real. That was the reason he photographed it. This was the evidence. Evidence, not for another, but for himself… evidence of the conclusion that he would rather not make or admit: he was not alone on the Bethlehem!

The arrow pointed towards Zone Gulf. It was the same direction that he was going. Following the point of the arrow James walked along the boardwalk for about twenty meters or so; finding nothing, not one foot print or scuff-mark; puzzled, concerned, and confused, James turned and went back to the train.

He kept to the schedule he had planned for the day — his Chlorella farm and two short naps. Tomorrow he would get the train moving again but the Chlorella farm was of primary importance — he needed to eat. James had discovered that he could reduce the strange nightmarish dreams that he had been having ever since arriving on the Bethlehem by napping, but not for more than an hour, or two hours at the most. He found, that if the naps lasted longer he would find himself in some awkward or disturbing place like the “chair” or the “high-jump.” During the night, in his heavier sleep periods, his dreams would get the better of him and the nightmares flooded back, filling his sleep with frustration and vigor. He did not doubt his earlier assumption: he was fatigued. And if he were fully truthful with himself he would also have to admit that he was more than a little bit frightened.

* * *

I always hate it when other officers salute me when I’m not wearing a hat. That was protocol. Not a high protocol, but a protocol all the same; people always seen to forget their basic training.

But still, the young Lieutenant stood, hand clinched to his forehead, waiting for me to return his salute. Annoyed I let him stand, and then an amazing thing, I looked down and saw I was actually in dress uniform. I was wearing a hat! I did not remember dressing in anything other than an inner pressure-suit with a light sweater over the top; my pajamas, so to speak — I had just gone to bed. Margret Allen had put the little ferry vessel into a path that cut a parabolic arc between the Maryland and central axis. We were weightless for some time; a novelty that could easily become a nuisance; but instead, we made the most of it. The weightless period lasted for only thirty minutes and we enjoyed a small game of hand-ball, substituting a pressure-suit helmet for the ball. Everybody but Weston joined in. It helped break the ice with Eleanor some. She was still angry with me. She had made only one snide comment on the subject since leaving the pump-house door where she encountered the raccoons: on reporting to Margret at the helm she said, “Press-ganged Tilney” reporting for duty ma’am.” Margret smiled at this and I couldn’t help but notice that Eleanor said it loud enough for me to hear.

After the little ship was put into the dive Margret and Eleanor floated back from the flight deck and challenged us men to the game of hand-ball. The game ended up, much too Weston’s chagrin, as a game of piggy-in-the-middle, Weston as the pig; a very grumpy one at that, I might add.

By the time we reached the central axis Margret and Eleanor returned to the flight-deck and ordered us to our beds, which, in all actuality was not a bed at all but a padded wall. These walls were the structural portions of the ship and were rarely used. But when used, they were used as beds. Because the walls were both structural and perpendicularly aligned with the longitudinal axis of the vehicle the gee–force of acceleration made it the most natural place to be during high stress maneuvers. These walls, or sleeping-walls as they were called, were specially designed beds but with a miniature hydraulic IV drip that inserted into our pressure-suits. A heart monitor, a blood pressure meter, and a blood oxygen reader were stock-standard in a pressure-suit’s inner liner, and the suit was able to communicate with the bed via wireless, monitoring our vital signs for undue stress. There were other controls on the bed as well. You could patch into FleetNet and check up on your favorite chess champion, or enter into one of the thousands of the online chess matches. Entertainment was only fingertips away. But what most people usually did was sleep. The IV drip could administer a special drug for longer flights and another drug to slow the body’s metabolism down, keeping all other bodily functions at bay for the duration of the flight. Considering the immense gee force on the body, there was not much else to do. A four gee-burn made the human body weigh exactly four times its mass. Mankind had not created a device that could counteract the natural force of inertia and so, a sleeping-wall was a reflection of that limitation.

It was forbidden to fly along the central axis even though it was the shortest distance from ship to ship. Axis flights were only approved for emergency or diplomatic flights. All other inter-ship traffic kept to the helical path and cyclical orbit of the Fleet. These last took longer of course, but were far safer; not only could ferry vessels ease in and out of a ship’s orbit more easily but they maintained a tolerable one-gee gravitation field for the duration of their passage.

As gee increased we three, Weston, Simon Allen and me grabbed some blankets and pillows from the locker room. We each found a wall to sleep on and plugged our suits in. As the gee-force increased above two point zero we were stuck and pinned against our walls as if on a dart board. I shifted heavily trying to make myself as comfortable as possible before things became inevitable worse. Margret’s flight plan called for slow acceleration to seven-gee which she would gradually slow back down to maintain a four-gee burn that would last for several days. At that point she would cut the engines and we would be weightless for a short time while she turned the ship 180 degrees to begin the whole process again; but this time our acceleration would be used to slow us down.

In my opinion, it is best to sleep during these types of flights and let the autopilot do the work. The sleeping-beds up on the flight-deck also contained some manual controls for the pilot to take control of the ship in case a problem arose. Margret and Eleanor remained on the flight-deck to pilot the vessel if need be.

The cabin lights dimmed, and I was just nodding off to sleep but by the time we reached seven-gee, I was fully awake. Seven-gee is a most unpleasant sensation, at best. It’s hard on the human body, and especially harder the older you get. I felt every bit my seventy-five years and I swear I heard my rib cage creak as the invisible hand of my own mass pressed against me. Eventually though, as the profile slowed to four-gee I pulled the blankets, which felt as heavy as divers weights, up about my neck and fell fast asleep.

So I knew I was in pressure-suit liner, and I knew I was not wearing my hat or uniform. But surprisingly, I was. The smartly dressed Lieutenant in front of me was still standing at attention waiting patiently for me to return his salute.

I touched my hat; the Lieutenant relaxed his arm and waited for me to speak.

* * *

I looked about. We were in a darkened room. The walls and ceiling of the room faded into soft smoothed edges, almost as if hiding a concrete edge from us. In the center of the room were a small round table and two chairs. An old fashioned lighting system hung precariously from a ceiling. I guessed that I was about to have another of my bad dreams.

“What is this place?” I asked the young officer.

“I hoped you could tell me sir.” He answered politely looking about.

The young man was thin, but not in an awkward way. He had a strong sinuous build and a pale complexion. He had the kind of forehead that reminded me of a thinker. His eyes were deep and sunken, blackened and sore from lack of sleep; as tired as they were they expressed softness and sincerity. Though, there was something more. I looked closer: haunted; chased, and anxious, might be a better description. A great fatigue hung upon this young man.

“Are you alright son?”

“Yes sir, I’m just very tired. I have not been sleeping well.”

I rubbed my hand across my own face and suppressed a yawn. “Me and you both son, and it doesn’t look like we’ll get much tonight either,” I laughed.

The young man grinned at my joke and I liked him all the more for it.

I held out my hand. “Councilman John Tilney,” I said introducing myself.

“Lieutenant James Rushworth, Navigation Officer 4th Class, assigned to the Rhode Island, Sir.”

“I know you! You’re the chess player, right?”

“Ah… Yes Sir.”

“I watched you play last year. You almost had it! That was a match to remember.” I said reminiscently rocking back on the balls of my feet, “that was a great game, and you were such a good sport about it.” Rushworth seemed a little embarrassed by my enthusiasm. I could tell that he didn’t want to talk about chess. The Fleet sport we call it — we all played it — some better than most. Rushworth was one of the best, if not the best. He just shook his head and said “I did my best sir. I hope to come back this winter and do better.”

“That’s the spirit.” Changing the subject, while pulling out nearest chair from the table, I said. “I wonder if these chairs are rigged?” Rushworth’s eyes widened at my inquiry.

“Why do you think that sir?”

“Well, I have been having this constant nightmare where I’m sitting in a chair that falls to pieces while a group of men and woman grill me with nonsensical questions. Apart from annoying, it’s a rather tiresome dream. I don’t like it at all.”

“I’ve had the same dream!” We looked at each other saying nothing for a few seconds. Then Rushworth asked, “Is this… is this a dream, sir?”

“Yes. I think it might be.” I answered looking about. I sat down in the chair unable to contain my own curiosity. “It seems stable enough.” I smiled at the Lieutenant, wriggling in my chair. When nothing happened he cautiously pulled out his own chair and sat.

“Where are you sir?”

“Excuse me?” I answered not sure what he was asking.

“I mean, where are you now? Really… where are you asleep?”

“Oh, yes. Good question. I’m on a ferry vessel heading for the Orion at high speed along the central axis. And you?”

Rushworth hesitated. I couldn’t tell whether my answer surprised him or not. After a few hesitant seconds he said, “I’m on the Bethlehem.”

Now it was my turn to be surprised. “You are where?”

Slowly, over the next hour or so, James Rushworth told me his story as I have presented it to you here.

Catherine Moreland had told me that she had travelled to the Bethlehem. I had assumed she was accompanied by a whole team of Fleet officers, with a wealth of skill-sets that could take on an abandoned starship. One man? This one man? His weariness was so worn in him, not just from nightmares but by the sheer necessity of his own survival. I saw that now.

I listened to Rushworth’s story in a fascinated kind of horror, as he alone, on the brink of starvation, plied his way through the icy-dark caverns of the Bethlehem. When he finished, he expressed his concern that he was now having dreams while awake. I asked him what he meant by this, and after some more urging he told me about the girl he had seen tight-roping her way along the boardwalk railing of the Bethlehem dry-dock. Then he showed me a photograph he had taken of the arrow etched into the dusty ramp floor of the boardwalk.

I took the photograph and stared at it. It did appear as if it was done by a finger. I looked carefully, trying to see if a discrepancy between the height of the dust in the immediate vicinity and the depth of the arrow existed. There was no height difference, eliminating the idea that the arrow had been made sometime other than the near present. Puzzled, I laid the photograph down in front of me and said, “The girl may have been a dream but this,” I said touching the photo’s edge, “defies explanation.”

“Do you know who Charles Harville is?” I asked Rushworth changing the subject.

“Yes sir. Captain Moreland gave me the details of Harville’s investigation into the oblation of Orion’s orbit.”

“Yes, I’m sure she did. But you probably didn’t see this…”

I reached into my pocket. “This is a synopsis of that same report – but uncensored by Moreland and her friends.”

Rushworth took the paper and scanned it. His eyes tightened, and he read it more slowly. After a few minutes he looked up and said. “This is not exactly what Captain Moreland told me. Nor is this text any part of the report I read.”

I laughed and shook my head. “Well that’s Catherine Moreland for you… What can I say?”

A flood of weight came upon me; I woke suddenly.

* * *

I was back where I should be. I opened my eyes to the dim cabin lighting of the ferry vessel; on the wall to my right, Weston was snoring loudly. Under the weight of the four-gee stress I rolled with difficulty to my side; I thought about the dream. It was as real as any of the other bizarre dreams that I had been having, but this time I had not woken covered in sweat, frustrated and angry. This dream had been rather pleasant. James Rushworth, I knew, was a real person. In fact, everyone knew who James Rushworth was. He was the gutsy young Lieutenant from the Rhode Island who bested some of the best chess players at last year’s Fleet Chess Tournament. Rushworth had made it all the way to the semi-finals; only to stumble badly in what could only be called a battle-royal with the reigning champ himself, the grizzled old Supercentenarian Peter Giles, and even then it took Giles almost seventy-two hours to beat him. The end came abruptly when Rushworth finally faltered, losing his Knight to Giles’s pawn, shaking his confidence. Rushworth hung in there for another five hours but even then, it was as good as over. James Rushworth was not someone who gave in easy. All-in-all it was a great game; the newcomer facing off with the more experienced old timer, an old story that James Rushworth played well. It was something that none of us who watched that game from beginning to end would forget anytime soon. It was great. The people of the Fleet loved it, and for a short time we all loved James Rushworth.

Yes. The tired and worn young man in my dream could very well have been that James Rushworth. But why on earth would I have a dream about this individual, amongst the tens of thousands of other Fleet personal? Like most everybody else, I had watched the tournament on FleetNet, I’d never even met James Rushworth.

I attempted to roll over once more but failed completely, flopping onto my back like a floundering fish. Four-gee is a difficult thing to fight, especially when tired. So I just lay there and stared at the bulkhead in front of me. Something crumpled under my right wrist. I looked at it, and with great effort picked it up and turned my face to see it. It was a piece of paper.

I think I stopped breathing for a whole minute. In my hand was a photograph of an arrow. An arrow etched into a thick layer of dust.

* * *

Through the intercom I managed to wake Margret and had her stop the cruise. The cessation of acceleration felt as if we had come to a complete stop; and without a rotational vector we were weightless again. Weston floated from his wall and banged into the bulkhead ahead and woke cursing us all loudly.

* * *

I decided I needed to talk to Catherine Moreland immediately. Or did I? I reached into my breast pocket searching for the decoded data on the Orion that Harville had prepared for me. It was gone. I floated, and for the first time in a long time, had no clue what to do next. The perplexed enquiries from Margret, Simon, Weston and Eleanor were my cue to action. This was impossible! Inexplicable and bizarre, I had no word or concept for it. I mused quietly for some minutes; everyone waited for me to say something. Finally, I made up my mind.

“Change of plans. I need to go to the Aristotle. Margret, Simon, Weston and Eleanor I need you to go on a rescue mission to the Bethlehem. But, I’ll need to confirm something with our friend Catherine Moreland first.”

Jaws’ dropping in zero-gee is an amusing phenomenon, but I did not have the temper for that just now.

“If you will all excuse me I need to speak with Catherine Moreland.”

I went up to the flight deck and closed the door. Working with one of the navigation computers I found her – but not where I expected to find her. She was on the Maryland! After about an hour and some haggling with Maryland’s duty officer Moreland appeared on the screen, cool and refreshed. Without salutatory introductions I spoke: “James Rushworth.”

A flash of anger darted into her eyes but as quickly as it had come it disappeared and her complexion paled; after some prodding she told me what she knew. Neither she nor her Bingley had heard from Rushworth since they had set him aboard ship. They suspected that Rushworth was dead.

I let Catherine tell me her story about the young Lieutenant without interruption. While she spoke, the horrible idea that I had somehow been having a conversation with the ghost of James Rushworth wiggled its way into the back of my mind, I pushed the thought aside, thinking of the photograph in my pocket. I let Moreland finish. Catherine, for all her outward toughness actually did have a heart. She and Bingley had packed a transponder and some specialized communication gear with which to communicate with Rushworth while he made passage through the empty bulk of the Bethlehem. They had lost contact with him almost immediately. Catherine felt that Rushworth was probably dead. I did not apprise her of anything different nor did I tell her of my strange dream. I signed off with a simple warning to steer clear of Charles Harville. I had made my judgment and expected no interference. She nodded in agreement, swallowing hard. I had no doubt that she was calculating her next political move. I had to smile to myself — she would leave no rock unturned to discover the person who gave me Rushworth’s name. It felt good to destabilize her some. I let her go with one last parting shot, but her answer rattled me somewhat.

“Catherine, you look like you could use a good night’s sleep.”

“True. I’ve not been sleeping well. Nightmares… you know.”

And then she was gone.

* * *

A photographic memory is a terrible thing to have, James decided. He remembered the day his parents died as if it was only yesterday. Those quiet distressed whispers between adults — uncles, aunts, and family friends. A photographic memory is a handy tool to have when finding point B, after starting from point A. But feelings: feelings of loss, sorrow and fear — and then those other feelings of: what do I do next? And, who’s going to look after me? They are hard; hard and unforgiving; as unyielding as stone, especially for a small boy with a photographic memory. The worse part, in the midst of such grieving, is feeling guilty for those same selfish feelings, and then reliving them in their immediacy almost every day since.

It’s all very well for the adults, their emotions are quick and old, and they know exactly where to store them when done. “…But, what about me? Who’s going to look after me now?” James dreamed restlessly — his fear — as real and as palatable as it had been on the very day he had been told his parents were not coming back from the lake. The most painful thing about memory are those things that are missing, or those things that were never there to begin with – but still existed; existed like a giant hole – a hole that should have been filled by his parents – but never could be. That hole reminded James of another empty space – the space inside the middle of a giant spaceship. The dry-dock of the…

When James woke it was his about his parents that he first thought, not the girl, or his quest for the navigation source code. It seemed that for the first time in a long time he had a normal night’s sleep. Yes. There had been that first dream in which Captain John Tilney, the Fleet Council Chairman appeared. But, his last dream, the one about his dead parents was disturbingly normal. It was a dream that he had on and off for years. Always, a refreshing day ensued. Disturbing the mind, on the things that it cannot dwell on during the day, always seemed to invigorate it. That, it seemed, was one of the strangest things about the human animal.

James lay in his makeshift bed of dismantled train berths; he dozed lightly. He thought about his childhood. It had not actually been a bad one, dead parent’s aside. It wasn’t that James didn’t have an extended family, he did. His father’s brother took him in and he grew up with his cousins — but of course, it wasn’t the same. He pushed his waking thoughts aside and dragged himself out of bed; making his way to the breakfast table.

Breakfast consisted of several cups of Chlorella from his bubbly little green farm. Chlorella tasted like liquid lettuce, which was to say that it had no taste at all. But that was not entirely true, it did have a hint of tin to it, metallic almost – though that could easily have come from the air-conditioning unit he had butchered to grow the stuff in. Either way, his breakfast was functional, serving to satisfy his base nutritional needs; but a steak – a thick juicy fresh steak from the dairy flats of the New Jersey – now that would be something! James put his fancy aside and cleaned up his bed and checked the Chlorella farm for any problems; satisfied that there were none, he checked the schedule for the day.

James had been trained well. Duty was Schedule and schedule was paramount to basic survival. It was true, for he was living proof. That thinnest of threads that strung long and taunt from the Primary Protocol: to kill Slugs; was the glue that kept James together. The Bethlehem, as daunting and as unyielding as she was, had not beaten him yet.

Today, James’s scheduled called for him to drive ten kilometers. This would the farthest he had driven the train in one day, a whole two platforms worth. Tomorrow then, he would only need one stop and he would be at the midpoint of Zone Gulf; his destination.

The platforms, or more properly, Train Stations, were interspersed at regular intervals of five kilometers each, by which passengers could embark or disembark. The Station could be accessed by the boardwalk by either one or two long flights of metal stairs. By spacing each platform at five kilometer intervals the makers had allowed for access into the ship through multiple Zones. James was currently parked at Station EF PORT, which simple meant that he was on the port-side of the Bethlehem at a Station that was exactly centered between Zone Echo and Zone Foxtrot. The next stop was Station FMID PORT; which is to say was the midpoint of Zone Foxtrot. James’s target was Station GMID PORT, which was exactly fifteen kilometers from where he was now. At a current average speed of one and one half kilometers per hour, James reckoned he would make Station FG PORT by late afternoon today, and then, after a night’s rest, without pushing himself or the train, arrive at Station GMID PORT by late morning tomorrow . This would allow him a quick reconnoiter of the air-lock into Zone Gulf, and the working and living spaces beyond before nightfall.

The train’s cockpit was a small cramped affair; a single stool and a minimum control panel. The vehicle’s master-computers were actually accessed through a small trapdoor in the floor beneath the stool. During his initial entry into the train he had spent many hours in and out of this trapdoor utilizing his own computer to communicate with the train proper and the Bethlehem’s computer-servers beyond. James now moved some of his cables aside and lowered the stool into position. He powered-up the train’s electromagnetic clamps, and using the thrust lever, accelerated the train tentatively along the tracks. With the trains powerful headlight he was able to see a good half kilometer ahead. But as the train began to move it kicked up a small dust cloud that reduced that his visibility to only a few hundred meters. As the train picked up speed the visibility only got worse. The murky gray mist that enveloped the train had been his constant companion over the last few days – but he supposed — it was better than ice.

James found he could swivel the train’s headlight. He swiveled it now, back down to the boardwalk towards the dusty drawing of his mysterious arrow. The distance was just a little too far to make anything out – but look he did – but saw nothing. After a few seconds the platform disappeared behind him in a halo of dust particles.

With the Station behind him, there wasn’t much to see other than the smooth black wall of the dry-dock. A few minutes out from the Station he came across a large contraption perched above the rails. The thing appeared to be clinging to the side of dry-dock by a series of giant clamps that looked like claws. James’s heart skipped a beat. Could this be a robot? Yes, he thought, taking in its ancillary limbs and wispy antennae, it was! James slowed the train to get a better look. The robot was an awkward looking thing. Large gripping forks stuck askance telescopic arms which now, with the device inert and dead, hung uselessly downwards from its body into the path of the train. James could feel the slight scrape above his head as the train knocked the robot’s appendages aside as if they were nothing more than pulled-taffy. James and his train continued on into the dusty darkness.

Robots were forbidden on the Fleet. The only ship where a real robot could be found was on the Bethlehem — and nobody goes there – James thought this last with a smile. He had grown up milking cows by hand; a laborious chore coupled with goat and sheep farming. James and his cousins had spent about one half of the day laboring on the farm and the other half of the day laboring in school. They had ridden horses to school – that had been fun — but horses needed cleaning and proper care too. The Fleet, James had learned, when he finally matriculated and attended the Rhode Island’s only University — which thankfully – to which he was allowed to travel to and from by train, was an economy of labor and trade. It was so well balanced that mechanized labor would disturb the natural order of life. James did not doubt it. The most mechanized device on his uncle’s farm was a wheelbarrow. The extensive long-life enjoyed by humans created a three tiered autocracy, from which there could be no deviation. The young, the middle-aged, and the old, all purchased their livelihood with their labor: the young, from birth to age seventy-four, whose duty lay in acquiring an education in their early youth, and then, becoming the Fleet’s officers and crewpersons. The middle-aged, seventy-five to one hundred-and-fifty — here — duty was to be found in the maintenance of the past – university’s, libraries, museums – they are the teachers and instructors of the Fleet – the keepers of all Fleet knowledge. And lastly the old, aged one-hundred-and-fifty and beyond, these last are the Fleet’s warrior-class. An elite and secretive group whose numbers are few. They move with impunity about the Fleet, rarely seen but always ready. It is the old who will fight the Slug when the Fleet arrives in Pleiades.

James, like all members of the Fleet was allowed to choose his own path in life, as long as he kept to the basic guidelines of age and place. He was essential free to do as he pleased. Consequently, James saw this current role of driving a train through the ancient dusty confines of the Bethlehem as part of his duty as an officer, obeying the Primary Protocol and a direct order from his superior officers, as an unquestioned task. But that other part of him – the intrinsic exuberance inside of him that was fascinated by computers and machines-controlled-by-computers, bubbled to the surface and begged him to stop the train and inspect the ungainly shaped robot. But instead, he pushed the idea aside and pressed on into the darkness – such was his training.

Intertwined within his nature James had a powerful inquisitiveness, that at some point during his formative years, had become passion when it came to things computerized, hence his college-track of computer programming and Net-gaming-math, both complex subjects with historic roots dating back to even before the creation of the Fleet. James wished he had time to inspect the strange robot with the dangling arms but knew his duty lay ahead, and so, to distract himself, he reached into his breast pocket to pull out the photograph of the arrow, but instead found two vaguely familiar sheets of paper with handwritten notes upon them, startled, he stared in utter disbelief at the documents.

TO BE CONTINUED…