Establishment of the Tribunal

Establishment of the Tribunal

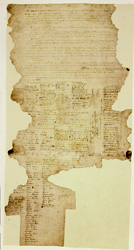

There is a long history in New Zealand of Māori protest over instances where the Treaty of Waitangi was not observed. The Waitangi Tribunal was set up in 1975 at a time when protests about unresolved Treaty grievances were growing and, in some instances, taking place outside the law. By establishing the Tribunal, Parliament provided a legal process by which Māori Treaty claims could be investigated. The Waitangi Tribunal inquiry process contributes to the resolution of Treaty claims and, in that way, to the reconciliation of outstanding issues between Māori and Pākehā.

The Tribunal’s Governing Legislation

The Waitangi Tribunal was established by an Act of Parliament, the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975. While that Act is the main statute governing the Tribunal, there are other statutes that regulate or affect how it works, including the Commissions of Inquiry Act 1908, the Treaty of Waitangi (State Enterprises) Act 1988, and the various statutes that give effect to Treaty claim settlements.

The Tribunal’s Offices

Generally speaking, the Tribunal prefers to hear claims in the areas to which they relate. Because of this, and because members live and work throughout the country, the Tribunal maintains only a small office, which it shares with the Māori Land Court. This office is located in Wellington, where the chairperson and deputy chairperson are based. The Tribunal also utilises the facilities of the Waitangi Tribunal Unit, which has its offices in the same building.

The Tribunal and the Legal System

The Waitangi Tribunal is part of New Zealand’s judicial system, which comprises a range of bodies, including:

- the general courts (including the District Court, the High Court, and the Court of Appeal);

- a number of specialist courts (including the Māori Land Court, the Family Court, and the Environment Court);

- various tribunals (including the Disputes Tribunal and the Residential Tenancies Tribunal); and

- temporary commissions of inquiry, royal commissions of inquiry, and so forth, which are established to inquire into specific matters.

The Waitangi Tribunal is unusual in that it was established as a permanent commission of inquiry. For this reason, it differs from a court in several important respects:

- Generally, the Tribunal has authority only to make recommendations. In certain limited situations, the Tribunal does have binding powers, but in most instances, its recommendations do not bind the Crown, the claimants, or any others participating in its inquiries. In contrast, courts can make rulings that bind the parties to whom they relate.

- The Tribunal’s process is more inquisitorial and less adversarial than that followed in the courts. In particular, it can conduct its own research so as to try to find the truth of a matter. Generally, a court must decide a matter solely on the evidence and legal arguments that the parties present to it.

- The Tribunal’s process is flexible – the Tribunal is not necessarily required to follow the rules of evidence that generally apply in the courts, and it may adapt its procedures as it thinks fit. For example, the Tribunal may follow ‘te kawa o te marae’. In contrast, the procedure in courts is much less flexible, and there are normally strict rules of evidence to be followed.

- The Tribunal does not have final authority to decide points of law. That power rests with the courts. However, for the purposes of the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975, the Tribunal has exclusive authority to determine the meaning and effect of the Treaty as it is embodied in both Māori and English texts.

- The Tribunal has a limited power to summons witnesses, require the production of documents, and maintain order at its hearings. But it does not have a general power to make orders preventing something from happening or compelling something to happen. Nor can it make a party to Tribunal proceedings pay costs.

— quoted from The Waitangi Tribunal’s website

Lots of problems with that. There was only one Treaty, not two. The only valid one is in the Maori language. All others are mis-representations, fakes, drafts, ‘fudged’ translations, and an ornate version for the benefit of the English Monarch of that era.

There’s a giant con-job going on. And Maori have the advantage, because they’ve planned better and are making good use of fifth columnists in government, have infiltrated academia and are using ‘bleeding heart liberal’ allies like D Coddington.

If you have a fifty dollar note, look at the portrait on it: Sir Apirana Ngata. One of the first (if not the first) Maoris to get a law degree. If you can track down his exposition on the Treaty, it makes fascinating reading. Reading not to the tastes of the Waitangi Tribunal, either, I suspect!

It also seems fairly well accepted (there is some proof) that there were people in New Zealand before the great canoe migration brought Maori to NZ.

Well, well, well . . . indigenous what? And guess who’s a member of the Waitangi Tribunal?