I referred in this post: Please read this NY Times column — ‘The Banality of Systematic Evil’ to the discomfort that ‘management’ can experience — and the poor decisions they can make as a result — when someone in their organisation highlights wrongdoing.

Remember?:

“… an accountant was dismissed because he insisted on reporting “irregular payments, doctored invoices, and shuffling numbers. ” The complaint against the accountant by the other managers of his company was that “by insisting on his own moral purity … he eroded the fundamental trust and understanding that makes cooperative managerial work possible.

The NZ Herald reported last month …

The detective who blew the whistle on his alleged drug-dealing boss was removed from his squad and investigated before senior police took his concerns seriously.

… the Weekend Herald can reveal the officer was removed from Blowers’ organised crime squad and put under strict supervision after he gave senior police management a report on his boss’ movements.

Disappointed colleagues say the disciplinary action undermines police attempts to encourage a culture where inappropriate conduct is reported to management without fear of reprisal.

The detective became suspicious of Blowers’ behaviour and tailed his visits to the home of a Whangarei woman before handing a dossier – which included covert photographs – to senior CIB management.

But instead of immediately probing Blowers’ movements, police management removed the whistleblower from the organised crime squad and placed him under strict supervision.

He was also subjected to an internal code of conduct inquiry which centred on his use of the National Intelligence Application computer system, which is supposed to be used only on official police business.

Several weeks passed until the detective was cleared of any breaches and attention later switched to Blowers, who became the subject of an internal inquiry.

That’s disheartening, isn’t it? I’m sure this sort of thing happens all the time, in organisations and businesses large and small.

Shooting the messenger

Journalist Glenn Greenwald, instrumental in bringing Edward Snowden’s astonishing revelations about illegal spying by the US government to light, points to the ‘demonization’ tactic some in power use when confronted with their own wrongdoing …

Ever since the Nixon administration broke into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychoanalyst’s office, the tactic of the US government has been to attack and demonize whistleblowers as a means of distracting attention from their own exposed wrongdoing and destroying the credibility of the messenger so that everyone tunes out the message. That attempt will undoubtedly be made here.

— On whistleblowers and government threats of investigation

In a (really depressing) article discussing why journalists working in Murdoch’s corrupt phone-hacking newspapers didn’t speak up Let the law save whistleblowers, not silence them, The Observer’s Nick Cohen warns:

Spill the beans on your company’s criminal activities and you’ll not just lose your job, you could lose your career

And it’s not just a problem with news organisations, as Cohen warns …

Ealing Hospital’s treatment of Sharmila Chowdhury typifies the insouciance with which NHS managers treat public health and public money. It sacked her on trumped- up charges after she accused two doctors of moonlighting. An industrial tribunal found in her favour, but rather than reinstate her, the Ealing Hospital NHS Trust prefers to waste taxpayers’ funds on paying her off. Like Moore, she has learned that when you challenge one hierarchy, you challenge them all. Sharmila tells me that she was about to land a job with another hospital when its HR department realised that she had broken the omerta of the NHS bureaucracy. The hospital decided it did not want her after all.

Glenn Greenwald makes a good point when he asks his readers to consider the alternative actions someone discovering wrongdoing in their organisation (public or private sector, no difference) could take…

… please just spend a moment considering the options available to someone with access to numerous Top Secret documents.

They could easily enrich themselves by selling those documents for huge sums of money to foreign intelligence services. They could seek to harm the US government by acting at the direction of a foreign adversary and covertly pass those secrets to them. They could gratuitously expose the identity of covert agents.

None of the whistleblowers persecuted by the Obama administration as part of its unprecedented attack on whistleblowers has done any of that: not one of them. Nor have those who are responsible for these current disclosures. [emphasis added]

The road not taken

I know of a situation where someone in an organisation discovered apparent wrongdoing and faced her superiors with evidence of the ‘irregular’ activities. After an initial shit-storm of abuse, bullying and threats towards her, she sat down around a conference table with the principals of the firm.

Over several hours, they talked through the issues, making some admissions, and in the end, they promised to look for a new way forward in continued discussions. The whistle-blower left that meeting cautiously optimistic that things could perhaps be sorted out. But, to her surprise, a few days later she received a thundering letter from the firm’s solicitors containing trumped-up charges against her (theft of ‘confidential documents’ ironically) and threatening criminal prosecution(!) Rather than admit their complicity, it seemed the firm’s principals decided to try to tough it out and dishonourably eject the whistle-blower from the business.

Yes, it’s a challenge dealing with a whistle-blower, as the examples above show. But how one does it can be extremely revealing of the ethics and ‘character’ of the people involved in the management of an organisation. (And, as we have seen, ‘good character‘ is quite important in some businesses.)

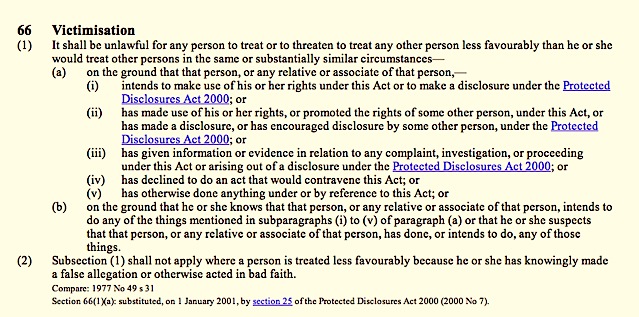

In New Zealand, we have a law called the Protected Disclosures Act 2000, which has provisions to protect whistle-blowers from persecution or sanctions of the type experienced by the person in that firm. The law refers to a citizen’s right to be protected from victimisation in these circumstances, protections also echoed in the Human Rights Act 1993 …

Interesting, huh?

– P

Don’t ever stop swimming upstream, Peter!

[…] to persecute, informants. (I’ve had reason to look at this recently. See my post ‘The challenge of dealing with a whistle-blower‘ which also, coincidentally cites […]